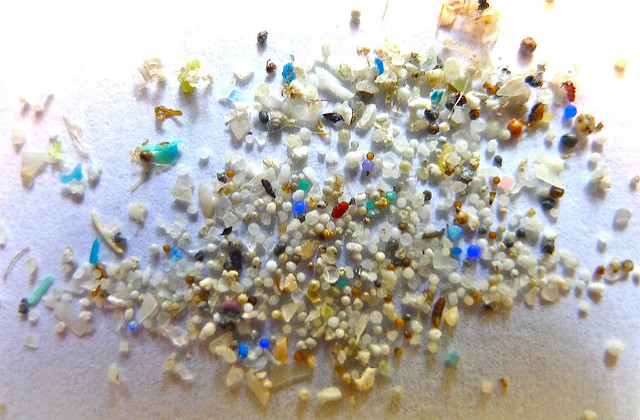

Microplastics (Source: Oregon State University on Flickr)

Lorna Shaughnessy didn’t move to Galway just to be a lecturer in the NUIG Spanish Department, she fell in love with the rugged Connemara landscape and crisp ocean waves crashing against the Burren. Now, years later, she is concerned about the increasing amount of plastic she sees washed up along the Galway shoreline.

“This is such a precious resource,” said Shaughnessy.

“We can be fooled into this sense of timelessness and timeless beauty, but it’s not timeless unless we take care of it, unless we value it.”

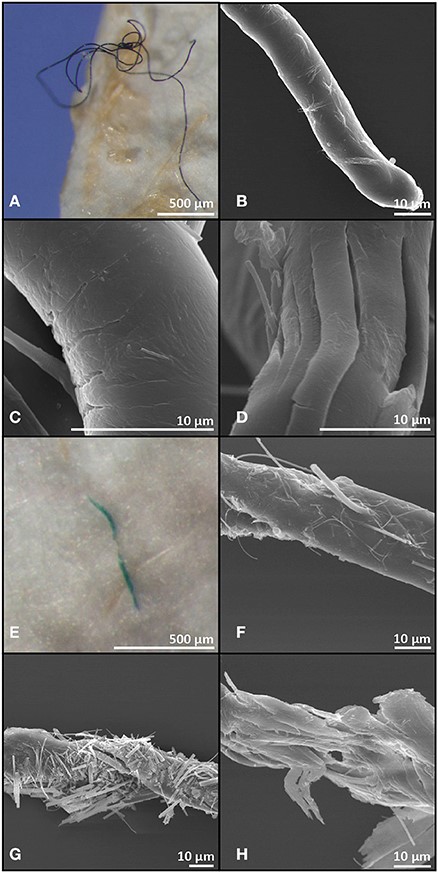

An NUI Galway study published last month found 73 percent of deep sea fish had microplastics in their gut. Researchers used sodium hydroxide to break down the biological material of 233 Northern Atlantic fish and filtered out microplastics that were left behind.

Microscopic images of microplastics found in the gut contents of deep sea fish. (Source: Frontiers in Marine Science journal, Frequency of Microplastics in Mesopelagic Fishes from the Northwest Atlantic.)

“My initial reaction was certainly surprise,” said Hannah Brownlow, an NUI Galway undergraduate in Zoology and Animal Science.

“The fish we looked at were caught in a remote part of the Atlantic Ocean, far from any coastal areas and yet the frequency of microplastics was one of the highest that has ever been found.”

According to Alina Wieczorek, lead author of the study and PhD candidate from the School of Natural Sciences at NUI Galway, humans don’t eat the fish that were studied, but they can work their way up the food chain and onto our dinner plates.

“Common predators of these fish are dolphins, sea birds, tuna and swordfish. We do eat those but so far there hasn’t been many studies on trophic transfer because it’s very hard to carry out these studies, to follow the plastics,” said Wieczorek.

For Wieczorek, this study is an opportunity for industries and individuals to become more aware of the harmful effects of plastic.

“For us it was very important to stick to the main message that the microplastics are found in such remote areas rather than scaring people without actually being able to prove anything,” she said.

“We just did a simple microplastic abundance study, it’s too early to infer too much from that.”

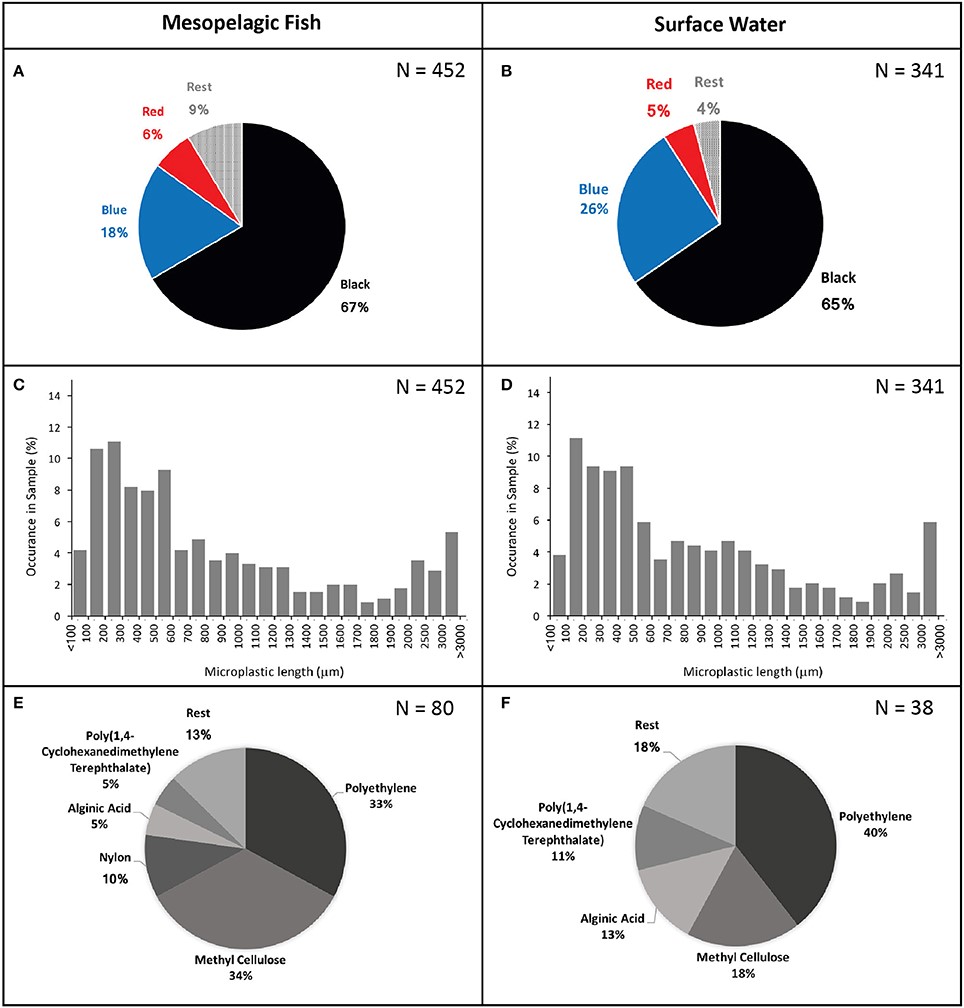

An analysis of the color, length and type of microplastics found in deep sea fish. Click to zoom.

(Source: Frontiers in Marine Science journal, Frequency of Microplastics in Mesopelagic Fishes from the Northwest Atlantic.)

Concerned citizens like Shaughnessy are looking for alternative solutions. She said the biggest problem she sees is plastic water bottle use by NUI Galway students. For Shaughnessy, this study is an opportunity for NUI Galway to take the lead in being Ireland’s first plastic water bottle free campus.

“It would be wonderful to be the first campus in Ireland that wasn’t selling plastic bottles of water, now that’s a very utopian vision,” Shaughnessy said.

“The biggest obstacle immediately is loss of income to retailers and caterers on campus, and I’m very aware of that, but I think we have to at least limit the number of one-use plastic bottles of water.”

Among other solutions, she suggested implementing water bottle filling stations that would have a small usage fee. “Surely it’s not rocket science,” she said.

Like Wieczorek, Shaughnessy believes our relationship with plastic needs to change.

“We’ve become so utterly dependent on plastic, we can’t even imagine our daily life in our own homes without it,” she said.

Shaughnessy reminisced about her childhood days going grocery shopping with her mother in Belfast, and remembers the simple ways that bread, eggs, and milk used to be sold. She said we have become accustomed to a packaged lifestyle and that we should go back to “pre-plastic” ways.

“Imagine a non-plastic day, it would start immediately,” Shaughnessy said. “What are you going to brush your teeth with? How many of us have a wooden toothbrush? There are wooden toothbrushes out there, but how many of us have them?”

According to Shaughnessy, being aware of our plastic use is important, but governmental sanctions will be a vital step to changing our consumptive culture.

“It’s not what we do as individuals, or what we achieve that’s going to make a difference, it’s the consciousness reason,” she said.

“There has to be individual responsibility but until we have real political commitment we are a drop in the ocean.”

Wieczorek said change can happen on both an individual level and a political level.

“Consumer choice drives industry. There will be a shift in the industry to target the consumers. If it’s driven from both sides, that’s where you get change.”

Brownlow takes an educational approach. She said that people should be made more aware of the harmful effects of the products they consume.

“In terms of where we go from here, I think it is important to look at the source of these microplastics and how we can prevent them from ending up in our oceans. The majority we found were fibers which probably came from synthetic clothing being washed in washing machines. But there is also a concern about microbeads which can be found in certain cosmetics such as face and body washes.”

The delicate beauty of Galway Bay is, as Shaughnessy said, timeless but delicate. While we might be faced with uncertainty in knowing how to approach the problem, the microplastics study is vital to drawing attention to our consumptive culture.

“I’m not saying it’s straightforward but we have to start thinking outside the box,” said Shaugnessy.

“In the absence of government measures coming down the road can a university at least find some leadership?”

By Claire VanValkenburg