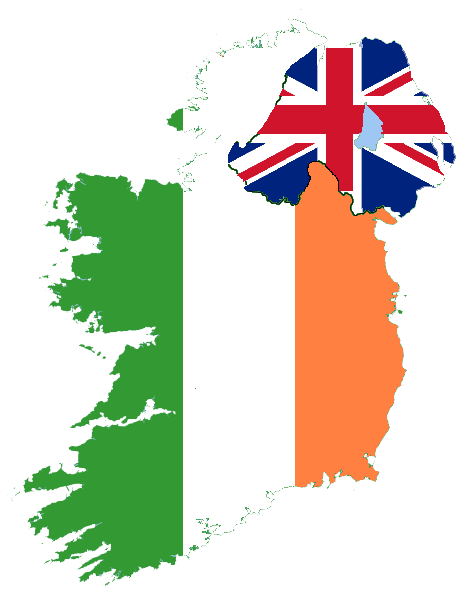

President Michael D. Higgins’ refusal to attend the 100th anniversary of the partition of Ireland and the foundation of Northern Ireland, caused a significant stir in political circles across our island. Many people across the Republic of Ireland overwhelmingly supported this call, even though the reasons for President Higgins’ refusal bore no semblance to many of the reasons offered by the public for its resounding support.

Partition was painful and led to civil war in the Republic until 1923, when a tornado of violence across the Free State eventually tempered. Its commemoration was always going to evoke that pain. In the North, those who identified as Irish suffered beyond what could have been anticipated – socio-economic discrimination, and state-backed violence.

The 100th anniversary of the foundation of Northern Ireland is an appropriate time to reflect on how the state has fared, but it’s also an appropriate time to use that historical context to frame discussions on its future. Has Brexit all but sealed the doomed fate of the United Kingdom? If so, what part will the Republic of Ireland play in what’s to come? Those questions are of crucial importance and can arguably only be answered with time, but the most important question is what do the people of Northern Ireland want for their future?

Brexit, the mess to beat all messes, was forced on Northern Ireland (and Scotland), without any consideration of how the UK would simultaneously manage a sea border within its own country, and a land border with a separate country. There is, as well, the added layer of repeated disregard by Brexiteers of the international peace agreement based on the fluidity of these borders, signed on Good Friday in 1998 by the UK and Ireland. The attitude towards issues related to Northern Ireland by those who voted for Brexit, and the Westminster government which has attempted to negotiate it, shows what we all knew already – they clearly do not care about Northern Ireland. That has been a difficult pill to swallow for Unionists, whose entire ideology derives from remaining in the UK.

The practical aspects of a United Ireland would need to be meticulously worked out pre-referendum… People need to know exactly what they’re voting for or against before a vote takes place. Making a United Ireland inviting for Unionists is going to take the utmost of compassion, understanding, and realistically time.

Yet the irony is that in attempting to vote for independence from the EU, Brexit has led to renewed and growing calls of votes for independence from the UK in Scotland, Wales and yes, even in Northern Ireland. For Scotland, it would be expected that a successful independence vote (unlike 2014) would mean economic, political, and cultural independence, as well as a back door into the European Union. Likewise for Wales. For Northern Ireland, it’s more complicated.

The calls for the North to leave the UK have never been based on it becoming an individual, independent entity, because they’re coming from a section of the population that believe they belong in a United Ireland. In any discussion, it’s implied, and in Republican circles explicitly stated, that a vote for the North to leave the UK is synonymous with a vote to create a United Ireland.

As well as this, Sinn Féin currently sits pretty at the top of the polls in both the Republic and the North. It’s an understandably concerning time for Unionists. A Sinn Féin programme for government here would have to include policy to achieve its goal of a United Ireland. The Irish public may not realise how close it is to having to make that decision. For Nationalists, they see this as the time to push through a United Ireland.

As Brexit showed us, the practical aspects of a United Ireland would need to be meticulously worked out pre-referendum – how will health, education, policing, parliament work? People need to know exactly what they’re voting for or against before a vote takes place. Making a United Ireland inviting for Unionists is going to take the utmost of compassion, understanding, and realistically time. Sinn Féin’s cavalier approach to such a divisive issue should be worrying everyone – not just Unionists.

Mainland Britain couldn’t care less whether the North stays or goes from the UK. The oft-used economic excuse from this side of the border not to form a United Ireland is that the Republic couldn’t financially support the North the way Westminster does. A study by DCU academic John Doyle, as quoted in the Irish Times, debunks this as mere myth. The Republic could be convinced to form a United Ireland if the terms were right.

Still unaddressed, however, is what Northern Ireland wants.

In 2019, about 50% of the Northern Irish population indicated they were neither Nationalist nor Unionist in the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, and that number is growing. They’re swayable either way on where the North goes from here. This includes an entire generation which has grown up after the end of the Troubles, believing in Northern Ireland as a modern and developed country, which doesn’t need to be British or Irish but can be both if they please.

Northern Ireland needs stability, harmony, and a collective voice from within, or 100 years of progress on peace is at risk.