The following article deals with themes of an adult nature which some readers may find upsetting.

During an interminably long lockdown, I’ve run a gamut of challenging books, both fictional and biographical. There is something magnetic about people who never compromise. Despite the hard realities that comes with it, the do or die approach to life is fascinating, and unsettling, to behold. Over the past few months two books have stayed in my mind. Disparate as they are from each other, they all concern people who have no other way of being anything but themselves, for better or worse.

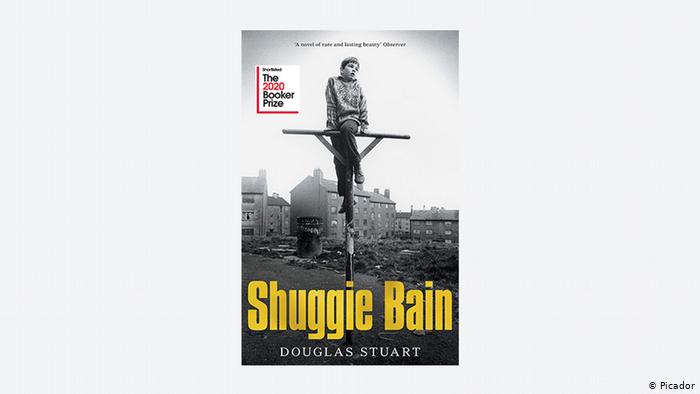

The most recent book was the Booker Prize winner Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart. Set in 1980s working-class Glasgow, the novel follows the titular Shuggie, the sensitive child of Agnes. After her abusive husband leaves her, she falls further into alcoholism and abject poverty.

Sexual violence, and its casual dismissal by others, is a constant. As Agnes tries to remember the details of a savage attack the night before, she shows the bruises on her arms to her friend and neighbour Jinty. Jinty coos faux sympathetically, “To do that to a defenceless wummin? What is this world coming to? The way people take advantage people.”

In a beat she asks Agnes, yet again, to go and find some money for alcohol, the only reason Jinty stopped by her home in the first place. The scene somehow gets worse when Jinty later makes Agnes, now in a dazed, drunken state, dance with the man who provided the booze. As she recoils away from him, Jinty, seeing how she can take advantage herself, shouts “Oh don’t mind her. She was just a bit unlucky in love last night”, says Jinty, knowing full well that Agnes was raped. This is a world where people don’t see others as friends or people deserving of love or respect, but as opportunities to use and abuse.

Exploitation is another constant in the non-fiction books. In Songs They Never Play on The Radio, writer James Young describes his time as a bandmate of Nico. Nico was a German singer and actor whose fame peaked during her time with The Velvet Underground. Her publicly long-running heroin addiction became better known than any sort of artistic endeavour. Which is a shame as her incredible music went on to inspire artists after her like Siouxsie Sioux, Elliott Smith, Robert Smith of The Cure and Bjórk.

The book depicts the last decade of her life with dark humour and clear-eyed lucidity. The band travels all over Europe not to be successful, but to feed her debilitating habit. While she falls further into addiction, her peers succeed with the same substance issues. Addiction seemed to give male artists like Lou Reed or Brian Jones a more rock and roll, glamourous image. For women like Nico, it was a black stain against her, a failure of femininity.

What stays in the mind the most from these books, read so close together, is the view of the female addict, as written by sympathetic men. In these books she is a figure caught between an uncaring society and their own demons. The repetitive nature of addiction; the nausea, the purge, finding the funds for a binge, gives the reader a hypnotic insight into the life of a person stuck in their own stasis.